Carin Smeaton

Kia ora Hana, You’ve been a busy mama! I’ve just finished reading your gorgeous little pocket-sized pukapuka ‘Blame It On the Rain’ and now I’m reading your third (and latest) ‘Some Helpful Models of Grief.’ I love the philosophies that you weave through your writings with the humour and socio historical threads that we writers from this part of the world tend to shy away from. I love that you don’t sanitise things and I love reading books that embrace that edge. Could you please let us Aucklanders know where you’re from and your connections to Tāmaki Makaurau?

Hana Pera Aoake

He uri tenei nō Ngāti Mahuta, Ngāti Hinerangi, Waikato/Tainui, Te Arawa, me Poutini Ngāi Tahu. Kei te noho au ki Kawerau. I tipu ake au Ōtepoti me Te whenua Moemoea. Ko Aoake tōku whanau. Ko Miriama Jean taku Tamāhine. Ko Hana Pera Aoake toku ingoa. Kia ora, my name is Hana. I’m from a bunch of places across Waikato, Tāmaki Makaurau, Bay Of Plenty and Te Wai Pounamu. I live in Kawerau, but grew up between Ōtepoti and many places in Australia. I have a three year older daughter named Miriama Jean that everyone calls Cheeky. I’ve lived in Tāmaki a bunch of times and I’m studying at AUT by distance, but my tūpuna lived and traded in Tāmaki throughout time. We lived at Ihumaatao for a while, as my great great grandparents were part of the Kīngitanga movement and were big supporters of Te Wherowhero when he lived here and he and my whānau are Ngāti Mahuta. On my pākehā side, my great grandfather had a tailors shop on Karangahape Road. My grandmother Margaret was from Tāmaki and grew up in Hillsborough before she moved to Matamata when she married my grandfather. I’m always learning more bits and pieces about my whakapapa, but it’s so interesting and grounding. Tāmaki Makaurau is a place I have lots of different connections to and love very much.

Carin Smeaton

I’ve always noticed your insatiable love of knowledges! The online initiative Kei te Pai press which you ran with co – editor Morgan Godrey greatly influenced my approach to my post graduate studies in information management. Which thinkers and people in general have influenced your views?

Hana Pera Aoake

Kia ora kia ora, Kei te Pai is on hiatus for awhile but it came about just before Covid and I think we just had more time to put energy into it and we didn’t have a kid. I think it’s more important than ever that we thread together different knowledge systems and ideas, because not only are we dealing with the legacy of colonialism and attempts by certain politicians to re-write those narratives in a way that obscures the lived reality of those histories, but even amongst our own people there’s a lack of cohesion or kotahitanga, which is worrying. The left is very fractured and while I think having different points of view is important, we must think collectively to ensure the core goals we have for what kind of future we want for our children.

Carin Smeaton

Ae! I often meet Indigenous guests visiting Central from other parts of the world and they’ve also shared your concerns about cohesion, well lack of it, in this world. I ask them for lists of books they think we should read and ones that Auckland Libraries should have, then I go request the ones we don’t yet have. I’ve requested a few books you’ve mentioned here. (So watch this space everyone!)

Hana Pera Aoake

We also are living at a time of witnessing genocide, which feels ridiculous to try and tone down or ignore. We have to understand the way these struggles for sovereignty and actually just dignity (housing, food & water, medical care, and work) are interconnected across the world and not just Indigenous communities, but all working class communities.

Carin Smeaton

Totally. Nobody can survive without these very basic human rights. The right to means to survive should not be a privilege or “given” for the few.

Hana Pera Aoake

No absolutely. I find myself reading a lot of the Jewish philosophers from the Frankfurt school, who were writing within the context of the rise of fascism in Europe and after the Second World War into the atomic age. I get pissed when people begrudge me for reading European writers, because I’m Māori , but I’m also Jewish and Scottish, so understanding the whakapapa of what happened there I think is vital in order to assess what is happening now. I’ve been re-reading Walter Benjamin’s writing especially Illuminations and I think his essay (which all art students tend to read) ‘The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction’ is pretty vital in determining not only what the purpose of art is, but thinking about AI. The most interesting part of his writing to me is when he uses the allegory of the angel of history in his book, ‘The concept of history,’ which is based on a painting his friend Paul Klee made. The angel’s face is turned towards the past, but where we perceive a chain of catastrophic events, the angel sees one continuous disaster that keeps piling up at his feet. The angel would like to make things whole, but a storm representing ‘progress’ propels him forward into the future to which his back is turned, as he faces the past. This makes me think of the whakataukī ‘Ka mua, ka Muri’ or walking backwards into the future. If we don’t understand the past we won’t understand the future. Hana Pera Aoake I also really love Simone Weil’s work especially ‘On The Need For Roots’ and ‘Gravity and Grace.’ The latter makes me think of wairua or this idea of two-ness or of being multiple, as in gravity is the material or bodily and grace is the non human or the way we might think about it could be the mauri of all things around us that has a whakapapa that stretches back to the separation of Rangi and Papa or the original two-ness.

Carin Smeaton

I’m glad you mention this – I see this two-ness coming through when I read your work – like I feel a sort of grief from this separation, if you know what I mean? Is this how your latest pukapuka got its name?

Hana Pera Aoake

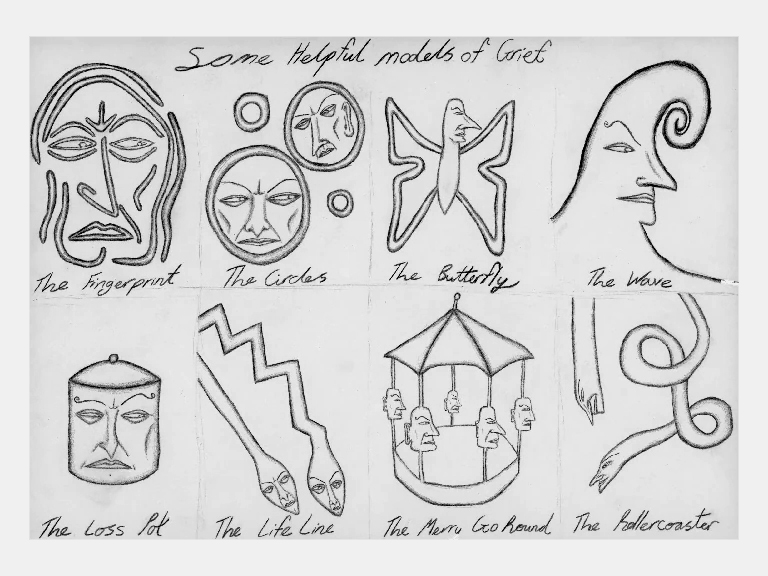

It actually got its name from an image I was given when I was in therapy after my grandfather died (Priscilla did a drawing of it but we ran out of time to put it in the pukapuka), but that’s a very interesting observation. I think the two most important writings I have re-read over and over is Dun Mihaka and Diane Prince’s book ‘Whakapohane,’ which details the trial Mihaka went through after doing a whakapohane I te tau to Princess Diana and Prince Charles in 1983. There’s a transcript of the trial where Mihaka defended himself and there’s such a tension between how the government saw this act as indecent exposure, but within a Māori worldview it’s a culturally sanctioned act that challenged the Crown’s authority and dispossession of Māori land and resources. Diane Prince’s work as an artist is very important for me. Her work acts as a pou for me in terms of thinking about specific kinds of loss, such as the cultural, political, social and economic implications of land alienation through colonialism for Māori. The second book is Ursula Le Guin’s pocket sized essay book, ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,’ which was an essay originally published in 1986 where she posits that not only was the carrier bag was the first tool invented by humans over the spear, but also utilises the carrier bag as a methodology for storytelling. I very much put lots of things in my kite to try to figure things out. I guess thinking of these two books as my own two-ness… Pākehā and Māori.

Hana Pera Aoake

What’s your approach to storytelling in your poetry?

Carin Smeaton

Mostly sensory – looking, listening, and song. Also memory – so very much like the whakataukī you mentioned just before ka mua ka muri. Hana, I also want to note the whakataukī you place at the beginning of your pukapuka – mā te ngākau aroha koe ārahi – let a loving heart lead the way. Can you tell us why you chose this whakataukī and what it means to you, my friend?

Hana Pera Aoake

So many of these poems I wrote and rewrote in the different stages of grief we go through when I lost people I love, which includes death, romantic relationships and when friendships broke down and ended. All of these were unique forms of grief and there’s a lot of different emotions you cycle through in those different kinds of loss. This whakataukī is a wero for me. It reminds me of the importance of compassion and of honouring the love I shared and felt for those people even if it has dissipated or it’s been many years or just yesterday. I think about it whenever I make any decisions about what I’m writing and what is a fair way to express that pain that doesn’t cause further harm, but still elucidates how I feel.

Carin Smeaton

In some helpful models of grief you mention or cite Aotearoa writers including, Keri Hulme, Māori Marsden, Moana Jackson, Talia Marshall, Khadro Mohammed – what’s special about these particular creatives and activists?

Hana Pera Aoake

I think every single person who lives in this country should read these writers. Keri Hulme was one of the first Māori writers I ever read, after Robyn Kahukiwa. The Bone People is a story that could only come from someone from Te Wai Pounamu with a deep understanding of the whenua, but also she wrote with so much tenderness even on topics that most writers could never touch like trauma and child abuse. I remember trying to talk to someone about this pukapuka and they couldn’t get past the abuse of a child, but for me it’s indicative of how these cycles of abuse are perpetuated by the reality of living in a colonised society and trying to locate your māoritanga. Even though there’s abuse, there’s still love and love is transformative. Māori Marsden’s The Woven Universe is essential I think to understanding a Māori worldview. I return to his writing over and over again and always find something new. Moana Jackson had such clarity and forcefulness, but his voice was so gentle. He never shouted, but his words were cutting. There’s a simplicity to the words he wrote, that belies that complexity of how he brings so many different ideas together. Talia Marshall is the best living Māori writer we have. She’s a brilliant storyteller who can speak to traumatic awful things that sting and then in the next line make you wet yourself laughing. She’s so underrated and everyone should buy her book, Whaea Blue. I still haven’t read Khadro’s novel, Before the Winter’s end. It’s sitting beside my bed, but her book of poetry, We’re all made of lightening, is brilliant and made me sob. It made me remember the way that this idea of whakapapa is something that can be made and remade and worn on your skin. Talia and Khadro are two writers who have really supported me and never just to flatter me, but to genuinely encourage me and tell me honestly what they think. They were both readers on my book and I’m grateful to them both.

Carin Smeaton

You include phenomenal illustrations from Priscilla Rose Howe. How did this collaboration come to be, if you don’t mind me asking?

Hana Pera Aoake

I’ve known Priscilla for years and we have collaborated on lots of projects. She was the designer for Kei te Pai for a while, until she decided to focus on her own work and we went into stasis. I love her mahi and asked her years ago if she would do illustrations if I wrote a new pukapuka. Her work is really layered and influenced by films by David Lynch, Peter Greenaway and John Waters, but also books like Story of the eye by George Bataille. I wanted to see how she would respond to my poems and I’m so happy with the result.